From the beginning, Self-Help's mission has been closely tied to the civil rights movement as we seek to expand economic opportunity for underserved communities. In honor of Black History Month, we remember many achievements by black leaders and innovators, and we also pay tribute to those who have fought for justice.

This week we have a guest post from Charlene Crowell, Communications Deputy Director for our affiliate, the Center for Responsible Lending. Charlene has been with CRL for 10 years, and during that time she also has been a regular columnist for the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), a trade association of more than 200 African-American-owned community newspapers across the U.S.

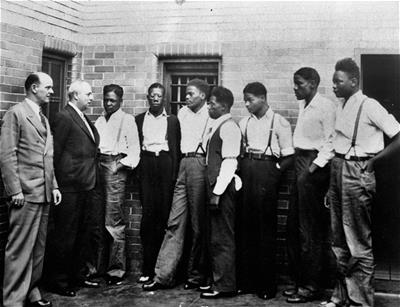

In 1933, the Scottsboro youths meet with their second attorney, Samuel Leibowitz with the American Civil Liberties Union.

A Brief History of an Injustice that Ultimately Changed Justice in America

The plight of nine young black boys who came to be known as the Scottsboro Boys, illustrates how elusive justice can be as well as a difficult journey that can take multiple decades. Even so, one of the accused nine Black youths spent 19 years in Alabama prisons for crimes he and the other eight defendants never committed. In the Jim Crow era, it did not seem to matter in a second trial that one of two accusers testified that the allegations were false. Or that their initial legal representation was laughable.

From the moment of arrest on March 25, 1931, all of the youths ranging in age from 13-19 insisted they were innocent of the rape of two white adult women they encountered after hopping a freight train, a common practice during the Great Depression in Alabama and across the country. During one of the re-trials, one accuser admitted lying about the crime.

After a three-day trial, an all-white jury convicted the Scottsboro Boys of rape. Legal representation for the youth was a challenge: no licensed lawyer in the state wanted to represent their defense. A real estate attorney from Chattanooga, Stephen Roddy, agreed to take the case and charged the parents a $60.00 legal fee, at the time, a sizable fee. But the only pre-trial services provided was a 20-minute meeting only minutes before the start of the trial. Roddy's advice: plead guilty.

With the exception of 13-year-old Roy Wright, the other eight were sentenced to death. In its deliberations, the jury was unable to decide whether Roy should be given life imprisonment or the death penalty.

The Scottboro youths with their parents, circa 1931.

Following years of appeals and more trials, in February 1935, the question as to whether Alabama could exclude blacks from jury service was the crux of the argument before the United States Supreme Court in Norris v. Alabama. The high court again overturned Alabama's court decisions, finding that the state deliberately practiced racial exclusion of blacks from its juries.

In 1937, four of the youths were released from prison. The remaining five remained incarcerated. On the fourth parole attempt, Charlie Weems, arrested at the age of 19, was released at age 31; it was November 1943 and 12 years after the original allegations. Two months later, Andy Wright, was freed and followed by the release of Clarence Norris and Ozzie Powell.

Haywood Patterson, was transferred to Atmore Prison Farm near Tuskegee where he worked 12-hour days on a prison chain gang. In July 1948 Patterson escaped with eight other Atmore prisoners, and on another train made his way to Detroit where he was reunited with family members living there.

When Andrew Wright's parole release came in 1950, he had spent 19 years and two months behind bars for a crime he never committed.

In October 1976, Alabama Governor George Wallace officially pardoned Clarence Norris. It was a pardon Norris had sought since 1946.

Charlene Crowell, Communications Deputy Director at our affiliate, the Center for Responsible Lending.